How we build our units

We believe young people shouldn’t have to stop being young people, just because they have cancer. So we asked young people to help us design our 28 units so we could build an environment that feels as much like home as possible.

Each of our 28 units in NHS hospitals across the UK is unique, but there are a few things they almost all have in common:

- Young people were part of the design process from the start, and their opinions and experiences were central to the decisions made.

- Taking care of the emotional side of cancer treatment is just as important the physical therapy, so we choose colours based on colour theory, a calm layout, and cosy furniture to make our units feel distinct from the hospital’s clinical spaces.

- Going into hospital takes away the normality of life, but the units counteract this with communal spaces where young people can socialise and hang out like they would at home, with friends and family or other young people going through something similar. You might walk into a unit and find a game of pool going on, someone gaming with friends, or a photography workshop going on.

Young people are critical to the unit design process

Mark Maffey is an architect, designer and project manager who worked with Teenage Cancer Trust on the design and build of Teenage Cancer Trust’s Southampton Unit. He spoke to us about how fundamental young people’s input is to developing specialist treatment centres for their age group. Read his full interview below.

Images from our units

This age group has a specific set of needs – they don’t quite fit into a healthcare system that caters for being either under or over 18. That’s why Teenage Cancer Trust’s drive to create-age specific environments is so vitally important.

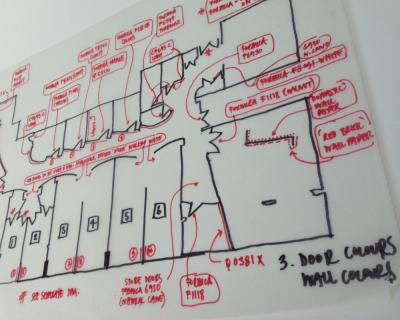

When we’re designing a unit, one of the key principles is involving young people from the beginning. We don’t want to produce a completed design then bring them in at the end of the process to ask “do you want this in blue or green?” Instead we allow them to influence the design from the outset.

For the Southampton Unit, we worked with a group of young cancer patients who had experienced a varied range of healthcare facilities. They joined the project at the very beginning, when the page was still blank, which was crucial to ensuring the unit was designed for young people by young people.

We worked together as a team over the course of a year to develop the design for the new unit. Our meetings were relaxed and informal, mainly in the evenings and often involving pizza! During the journey we built trust and respect in each other as people, which fostered an environment of openness and sharing – qualities which proved vital to the evolution of the design.

During the first session we spent our time getting to know each other, learning about their experiences, where they’d stayed, how they’d been treated and what their thoughts about their care might mean for a future unit.

At the following sessions we continued not to table any design proposals, but shared photos of a wide range of existing hospitals and watched and listened to their reactions. Initially the responses were centred on practicalities and logistics, but as the sessions went on they revealed far deeper personal stories and experiences.

We learnt that the young people felt emotional responses to the various ‘places’ in their unit, seeing the bedroom space as a place to be cared for, a place for wellbeing and healing. In contrast the treatment spaces were spaces with a bit more edge, places where you face the true reality of what you’re being told and what’s happening to you.

Rather than try to soften the clinical areas their view was to accept and make clear the differences between these two very different types of space. The resulting design shows natural materials, and smooth curving lines and a gentle but solid homeliness associated with the bedroom zone, contrasting with a more ridged, sharper angled feel to the clinical spaces.

For the social space the young people’s thoughts showed a clear consensus: make it like a common room, a bar, a shared kitchen, with sofas to chill out in, a big TV to watch films and football matches, a juke box and a pool table. Put simply – give us a space with the essential kit that makes us feel normal, that provides us with the things that being in hospital normally takes away from us.

When it came to the use of colour the young people made a clear association between bright colours and clinical spaces and themes, like staff uniforms, medical forms, sharps bins, the drugs they took. For the bedrooms they saw and felt clear links with calming colours and natural materials, and the final design for the unit both respected and responded to these feelings.

Then there was the question of how we brought these two spaces together. Young people told us that entering a cancer ward was like joining a club you don’t want to join, taking you away from your normal life and very much not part of your plan. So we came up with the idea of a line that runs through the length of the unit’s corridor floor and is emphasised by the single light fitting running above.

This line runs from the reception counter, and leads the new patient from the very point of arrival directly to the social space – the place where normality resumes. It says, “you are here, you may not want to be, but walk this line between the clinical and the healing spaces and you will end up where you want to be, where you came from – the place where things are normal again.”

The art simply had to be chosen by the young people – who else would be better qualified? To make this possible we prepared hundreds of postcards sized artwork images – photographic, modern, fine art, graffiti, cartoon, pop art, abstract, figurative, heavy oils, and typographic. We poured them on to the table, sat back and watched the young people sift through them.

One of the young lads picked up a picture of Durdle Door beach in Dorset, and the whole team became very engaged, the photos of the local area sparking memories and conversations of holidays with their family, warm memories of an earlier life.

We heard that the young people did not want inspirational photos of far flung desert islands, or night time photos of major cities - they wanted photos of their local area, and the realness that surrounded them just outside of the hospital grounds, somewhere they had been to and would return to soon.

This led the design of the corridor area to look like series of postcards, as if previous patients had sent in photos from their local area – an affirmation that the world was still there, and still normal. The whole wall has since become a point to just wander along, a place to spot and image to trigger a memory and a story shared.

As for bedrooms, the young people recognised that every patient’s needs would be very different, so prescribing art was one prescription too far. So we agreed to fit the spaces with large areas of blank (magnetic!) canvas – so patients could personalise their space - and to date this has proved a huge success.

Designers too often think they know best, and seldom are comfortable with allowing others to take control of the design process. For some the thought of a group of unqualified young people seizing control would be a worrying prospect, but our view was different. Surely the very people who will use the unit, and have used such units before are by far the best people to advise and the best to critique. For us the idea that we needed to listen to the young people, and listen fully, was the absolute bedrock of the whole design process.

We established a proper rapport with the people in the group and there was a real sense of teamwork. Unquestionably the unit wouldn’t be what it is today without their input.

Everything – layout, design, artwork, furniture – was driven by what young people wanted, and not just based on whimsical ‘wants’, but based on clearly defined and perfectly articulated ideas honed from very real experiences.

It was a real privilege to listen to and share the very personal stories of these remarkable individuals. It was tough and emotional at times. The experience for us all was very powerful, and the trick was to somehow harness the depth of emotion and experience, and turn it into something real. Time will tell if we got it right, but on the day the unit opened the team of young people who had worked with me throughout the whole process visited the unit, seeing it for the very first time. At the end of the tour one of the young lads turned to me and said, “we totally nailed it”.

That was everything I wanted to hear.